When I was a child in grade school in the early 1970s, we would recite the Pledge of Allegiance every morning. We would dutifully stand beside our desks, our hands over our little hearts, face the flag, and intone:

I Pledge Allegiance

To the Flag

Of the United States of America

And to the Republic for which it stands

One Nation

Under God

Indivisible

With Liberty and Justice for All

Then we’d sit and start practicing our penmanship (that’s cursive handwriting, for you younger folks).

In a time when we no longer even need to be capable of producing a legible signature, penmanship is obsolete; even quaint. And the Pledge of Allegiance? It occurs to me that a younger generation might be horrified by this regimented daily performance of patriotism by children; not to mention its invocation of the supreme being. But looking back…there was something centering and reassuring about it. It brought a bunch of hyperactive kids to order and started us off on the same page for the day.

I think that’s how I once, in my boyhood innocence, thought of patriotism and American ideals: there was a kind of faith at work. Believing that oaths like the Pledge were solemn things made the world feel ordered in some comforting way. One wonders…does that kind of wonder—a child’s wonder—exist anymore? Or a sense of American idealism? In a time when statues are toppled, the Founding Fathers villainized, the school curriculum “de-colonized,” that brand of innocence hasn’t a chance. On the other hand…perhaps that’s the eternal American struggle: idealism grappling with cynicism and corruption for its survival.

Nowhere in the past century has that struggle been more eloquently and movingly represented on film than in Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes To Washington, from that year of all years in the movies, 1939.

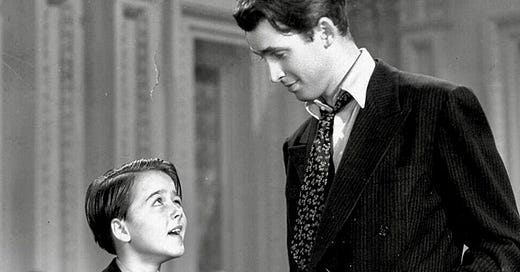

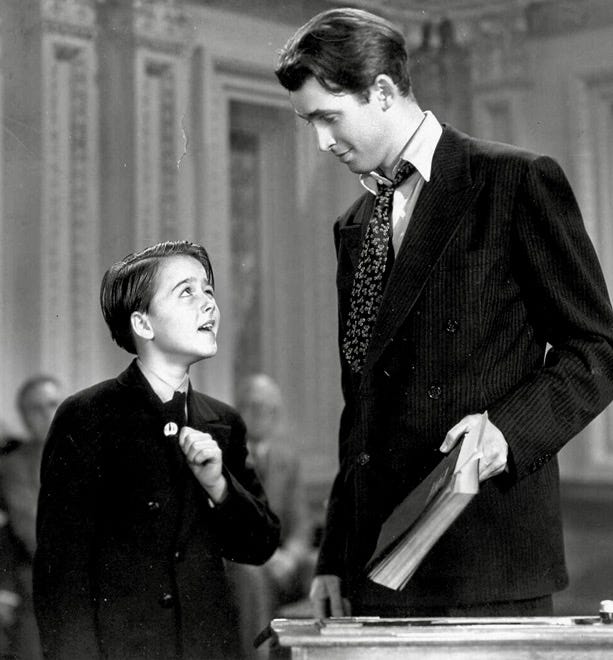

Boys abound everywhere in this film. They play a major part in the unfurling of the story, and in its resolution, unresolved as it may be. It’s the sons of Governor Hopper (Guy Kibbe) who nominate young Jefferson Smith (James Stewart) for the Senate seat that Hopper needs to fill. Early in the film, Hopper’s eight kids—six of them boys—trumpet the virtues of Smith: the head of the Boy Rangers, the hero who single-handedly put out a forest fire, a man who can quote Washington and Lincoln by heart, “the greatest American we got!” who inspires millions of boys nationwide with his publication, Boy Stuff. Hopper’s little boys speak convincingly about the corruption in their state, under the sway of corporate mob boss, James Taylor (Edward Arnold) and encourage their Dad to rebuild his reputation by bringing their hero, Jeff Smith, to the Senate.

The boy’s pleas are answered when Gov. Hopper proposes Smith as a useful dupe to Taylor and esteemed (but corrupt) Senator Joseph Paine (Claude Rains). Paine doesn’t realize, until encountering young Smith at his nomination banquet, that he was once great friends with Smith’s father, who was assassinated by mobsters when he got too close to exposing their operations. The Mr. Smith we never meet was a hero to both his son and his onetime friend Paine, a man of principle who believed that “lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for.” In a film full of boys, it’s natural that a strong theme of fathers and sons undergirds the entire story. Jeff’s Boy Rangers present him, adorably, and en masse, with a monogrammed briefcase: a grown-up going away gift.

When we meet Jefferson Smith, we see immediately why the boys adore him so much—he’s little more than an overgrown boy himself. Tall, gangly, awkward, Jimmy Stewart’s Smith is a wide-eyed bumpkin with an incredibly naive American idealism—with which we instantly fall in love. It’s a tough assignment: originally intended for Gary Cooper (who will, two years later, play the same character, essentially, in Capra’s Meet John Doe), Stewart brings all the ‘aw shucks’ required, but with a completely believable, brilliantly delineated innocence.

Through Smith’s eyes, we are treated to an essential civics lesson wrapped in a human drama. A total outsider, Smith, upon arriving in Washington, D.C., gets his first glimpse of the U.S. Capitol, and almost involuntarily moves toward it, following some patriotic siren song which leads him ultimately to the hushed and hallowed temple of the Lincoln Memorial. As Jeff marvels at this titan representation of his idol, a little boy, holding the aged hand of his grandfather, reads aloud the words to the Gettysburg Address carved into the monument. Looking to his other side, Smith sees an elderly black man enter, his hat over his heart as he gazes upon Lincoln’s statue. Words that Jefferson Smith could recite by heart to his Boy Rangers suddenly take on worlds of new meaning for him. This is the beginning of what will be Smith’s coming of age, from boy to man—the core of Capra’s film.

Arriving at the Capitol for his first day in the Senate, Smith is shown his desk (once used by Daniel Webster!) by a snappy young page, played by Delmar Watson. Our civics lesson continues as this smart kid shows Smith where all the action happens in the various tiers and balconies of the Senate, topping off his presentation with a wink and a ‘go, get ‘em!’ vote of confidence. Again, a boy is reminding Smith of the ideal view of America he’s brought with him from the back woods of his home state. Unfortunately for Smith, his pet project, his first proposal to the Senate, which is all about the back woods of his home state, runs afoul of the graft of Taylor, in cahoots with crooked Senator Paine. The spot Smith proposes for his national boy’s camp is the exact one where an unnecessary—and highly profitable—dam is set to be built. Smith’s ideals are about to be shattered. In a wonderful scene with Jean Arthur as Clarissa Saunders, Stewart delivers a moving monologue about how boys should be raised to regard their American inheritance:

You see, boys forget what their country means by just reading “The Land of the Free” in history books. Then they get to be men they forget even more. Liberty's too precious a thing to be buried in books, Miss Saunders. Men should hold it up in front of them every single day of their lives and say: I'm free to think and to speak. My ancestors couldn't, I can, and my children will. Boys ought to grow up remembering that.

Our “anti-patriarchal” times would ask, annoyed, “Why just boys? Why such an emphasis on boys? What about girls?” Well, I think, first look at the creator of this film, Frank Capra: an immigrant success story for the ages. The son of Italian immigrants, his trajectory as a film maker began with the very invention of the movies, the creation of the studio system and the Hollywood dream factory. Capra was living proof of the promise of America, the land of opportunity. In 1939, there were no women in the Senate. That being the case, and this being a story about American ideals confronting corruption in the U.S. Government of 1939, it is of necessity a story of boys and men.

As the film reaches its stunning climax, Smith holding the Senate hostage with a filibuster as Taylor’s network of thugs and corrupt newspapers blacken his name and prevent his home state from learning the truth, the boys put it all on the line for their hero. In a shocking scene of violence (which, among other aspects of the film’s exposure of corrupt practices in the political sphere, moved certain high ranking politicians to try and get the movie suppressed), a crew of boys attempting to deliver the real news to Smith’s constituents are run off the road by Taylor’s thugs. The boys in the Senate chamber, eyes glistening with tears, fix their gazes upon a rapidly weakening Jeff Smith, willing him to hold on, even as he rips through bushels of hate mail, the result of Taylor’s hit campaign in the press.

Honor does ultimately win in this remarkable contradiction of a motion picture: the clear-eyed cynicism of its snappy satire conquered by its unrelenting and obstinate faith and idealism. As Smith collapses from his herculean effort to stand against raw power, Senator Paine feels the pain of his disgrace, attempts suicide, and finally erupts into the chamber, passionately proclaiming his guilt and Smith’s innocence (in a scene which, if there were any justice, should have earned Raines an Oscar). He even goes so far as to refer to him as a ‘boy:’

Every word that boy said is the truth! Every word about Taylor and me and graft and the rotten political corruption of my state! Every word of it is true! I'm not fit for office! I'm not fit for any place of honor or trust! Expel me, not that boy!

The film ends with chaos in the Senate, a complete hootenanny, in which we see, for the first time in the picture, little boys jumping up and down, acting just like—well—little boys. A purification has taken place in Capra’s imagined Capitol: the corruption has been exposed, the righteous have prevailed, our ideals have won. Men are in charge once more, and boys can now be free to frolic and play again. Despite ruffling some official feathers and sparking controversy in the press, Mr. Smith Goes To Washington was enormously popular and, within just a few years, it became enormously important to morale—and not just American morale. The film was predictably banned in Nazi Germany and in Mussolini’s Italy, but it managed to be the final American film that slipped into Paris on the eve of the Occupation. The rousing American patriotism and theme of virtue triumphing over evil and corruption was so reassuring to Parisians, that one cinema, in an act of defiance, ran the film continuously for thirty days after the ban on American films was enacted. It’s pretty clear why Capra became Propaganda Minister for the U.S. once we got into the war.

At his lowest ebb of confidence, before Smith takes his destiny—and a filibuster—into his hands, he is spurred on by Jean Arthur’s Saunders. This speech sums up anything I could put together to sum up my feelings about Mr. Smith Goes To Washington and its importance to our national soul and story. It speaks to that spirit of obstinate innocence from which a kind of faith might arise:

Your friend Mr. Lincoln had his Taylors and Paines. So did every other man who ever tried to lift his thought up off the ground. Odds against them didn't stop those men. They were fools that way. All the good that ever came into this world came from fools with faith like that. You know that, Jeff.

You can't quit now. Not you. They aren't all Taylors and Paines in Washington. That kind just throw big shadows, that's all. You didn't just have faith in Paine or any other living man. You had faith in something bigger than that. You had plain, decent, everyday, common rightness, and this country could use some of that. Yeah, so could the whole cockeyed world, a lot of it.

Remember the first day you got here? Remember what you said about Mr. Lincoln? You said he was sitting up there, waiting for someone to come along. You were right. He was waiting for a man who could see his job and sail into it, that's what he was waiting for. A man who could tear into the Taylors and root them out into the open. I think he was waiting for you, Jeff. He knows you can do it, so do I.

I wonder if Mr Smith Goes to Washington helped to inspire the college students who arranged for Wendell Willkie to be nominated for the GOP in 1940. As you may know --Willkie never ran in a primary and was a pure write in candidate. They went through huge amount of ballots and eventually he was chosen.

Willkie of course was not isolationist at a time when the GOP was very isolationist. He came close to winning, but more importantly he reshaped the GOP to be far more outward looking.

Given what Jimmy Stewart did in WW2, I always think Mr Smith was the sort of character he played from the heart.