Innocence, once lost, can never be regained. Darkness, once gazed upon, can never be lost. ~John Milton

Salvatore Broschi died that Fall of 1717, quite suddenly and unexpectedly. He was a man in his prime, only thirty-six. His grieving family was panicked. Without their father’s income, it would not be long before they faced financial ruin. Some action had to be taken. Riccardo, the eldest son, had not yet completed his music composition studies and his future career depended upon that achievement—he could not abandon that.

His brother Carlo had a gift: he was born to sing; his pure, clear soprano like a bell. Even at eleven, he was ambitious, single minded. All he wanted to do in life was sing. Carlo was already the protégé of the greatest singing teacher in Naples: Maestro Nicola Porpora, who predicted extraordinary things for Carlo. He could soon be presented at court, where his talents could bring him employment at the highest levels—and gold to secure the family’s future.

Carlo once came to Porpora very upset. He had heard that another of the Maestro’s students, Caffarelli, had inherited a fortune at the age of 10, and had used his gold to buy a miracle. Weeping, Carlo begged him to disclose how God had preserved Caffarelli’s voice. The boy was terrified of losing the one thing in the world he loved: his singing.

Porpora had related this anecdote to Riccardo, in the months before his father died. He’d added, pointedly, that Caffarelli’s accomplishments, his life of prosperity and success, could not have been possible but for the…intervention.

For many nights, Riccardo prayed, begging God for a sign: Help me to preserve the gift you blessed my brother with. Help me to know this is for the best.

Whether the sign appeared or not is unknown.

The decision was made.

The dairyman had looked Riccardo up and down suspiciously, as he handed him the two buckets full of milk, steaming in the chill morning air. Once Riccardo had prepared the bath, he crept into his brother’s room and gently nudged him. Carlo stirred, sleepily allowing himself to be lifted and carried to the bath.

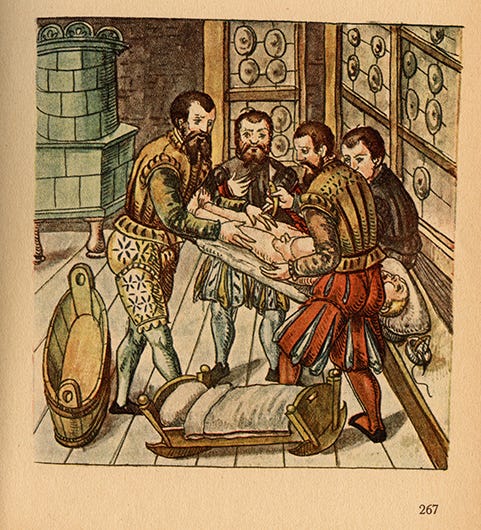

Submerged to his waist in the milk, drowsy Carlo drank from the bowl Riccardo held to his lips. The opium would take effect quickly. Riccardo sat there, tense, watching his brother as his consciousness slipped away—there’d been many cases where boys had died from too much opium. Carlo’s head dropped to his chest. His breathing was audible. He was sleeping.

Riccardo rose, trembling slightly, and drew from his belt the small thin blade he had sharpened that morning. He crossed himself, breathed deeply, and moved to the bath and his sleeping brother…

The agonizing recovery took two weeks. Carlo was bedridden, and regularly given small doses of opium to keep him semi-conscious and beyond his pain. The story Riccardo told the family was of Carlo being thrown from a horse. The damage from the fall…left him no choice. The elderly aunts and uncles nodded, impassively. They had all heard such stories. No one questioned it. It was for the best.

Within the space of two years, Carlo would become famous throughout Italy. He was known simply as il ragazzo: “the boy.” With his sweet soprano, and his slender shape, he often performed en travesti: the illusion of femininity complete. In Rome, he dazzled the court, and his meteoric rise began. Carlo would become one of the greatest opera singers of the 18th century, praised for his virtuosity, flexibility and vocal range—the voice of a boy…of a woman…of an angel. Nicola Porpora would rhapsodize about his star pupil, calling him “uno su un milione!” One in a million.

He came to be known as Farinelli.

He certainly had advantages that other castrati would never have: a family pedigree, the finest singing instructor in all Europe, and prodigious talent. Many thousands of other boys like him were not so privileged. The Church publicly and vociferously denied sanctioning the castration of boys…nevertheless, with the cavernous cathedrals of Italy to fill with song—and women forbidden to sing in public—the clear, bright voices of the castrati were highly prized. They filled up the ranks of every choir in the land.

Many more boys died of complications from the barbaric methods used to cut away or crush the testicles. Many bled out, or developed fatal infections. Many were lost to overdoses of opium, erratically administered, to sedate them for the procedure. The more primitive (and cheaper) method of squeezing the neck, putting pressure on the carotid artery until a boy became unconscious, would often result in asphyxiation. So greedy for the status and fortune a castrated boy might bring, families were willing to risk his death to achieve it.

The great Farinelli—“uno su un milione”—did not suffer that fate. He retired from his illustrious singing career at thirty-two, but lived well into his sixties. With no male hormones, his bones were unusually soft. His limbs grew abnormally long; his ribs were flexible and expansive, giving him near superhuman lung power. With almost unlimited breath support, and his child’s larynx, that high, clear mezzo voice would flow forth from the body of a tall, graceful man.

Offstage…Carlo lived the life not of a man, but of a shadow.

He developed breasts. He exhibited the symptoms of female menopause. His soft bones became brittle with osteoporosis. Despite popular erotic myths about the powerful sexual prowess of the castrati, Carlo’s penis was tiny, and he experienced little to no sexual desire. The courts of Europe were rife with tales of ladies in his audiences, who, ecstatic from Farinelli’s singing, would spontaneously climax. The great singer himself never once experienced orgasm. There were scores of admirers. The titillating rumors of Farinelli’s many love affairs abounded. But Carlo lived each and every day of his adult life carrying in his heart the sorrow that he would go to his grave childless.

Riccardo, tormented with guilt until the end of his days, would blurt out to anyone who’d listen the story of the terrible sacrifice he’d made for God. The sin he had committed to preserve his brother’s heavenly gift, his voice God’s gift to the world. Forgotten was the lie about an accident and a horse. He would insist that Carlo wanted it, that he had begged for a way to keep his voice.

From the moment the boy Carlo rose from his bed of pain, recovered from the agony he’d endured from Riccardo’s “sacrifice,” and set out into the world to become Farinelli…

He never spoke to his brother again.

Only those who must bear the consequences of a decision have the right to make it. ~Starhawk

The Horror of the world was that thousands of evils fell upon innocent people, and no one was punished and with great promise there was nothing but pain and desire Children mutilated to form a choir of seraphim. Their song was a cry to heaven the sky was not listening.

~Anne Rice, Cry to Heaven

One of the first and strongest trends you'll notice, if you look at portraits of Farinelli and other castrati, is that ALL of their faces become indistinguishable from those of normal, anatomically and hormonally intact men by age 30.

Their arms and legs are proportionally LONGER relative to the rest of their bodies, too... and they're taller than average men, too (since pubertal testosterone is the main factor cutting off the height growth of teen boys). They end up built like men with Marfan's syndrome (look up if you're not familiar).

(These last couple facts surprise many, but have actually been known since PREhistory—as far back as neutering has been used as an animal husbandry technique, meaning AT LEAST as long ago as the very earliest proto-hieroglyphs on rock walls: Steers are bigger and taller than bulls; wethers are bigger and taller than rams; geldings are bigger and taller than stallions; etc. It's about as obvious as analogies get.)

Women's arms and legs are noticeably shorter on average than men's, so, by the time eunuchs are in the heart of their young adulthood, their appearance is the exact antithesis of "femininity"—and will stay that way for the rest of their unusually long lives (they outlive normal men on average, because low testosterone and lower body weight protect them from heart disease).

To see the end-stage facial masculinization and long, gangly, decidedly un-"feminine" limbs (starting to suffer dysplasia and spontaneous dislocations) in real life, just look at "slut pop" singer Kim Petras, who was neutered as a "trans teen". Petras is now a 31 year old man with an ever-growing slate of health problems—severe enough for him to have cancelled all his concerts for last year and this year—caused by long term excess of extrinsically supplied estrogen... and he looks every bit the part (i.e., like a 31-year-old man with severe health issues).

It is such a heart breaking tale. Carlo had no idea what he was asking for when he wanted his singing voice to be preserved. More than likely his adult male voice would have been wonderful as well.

There were the castrati and even before that, the priests of Cybele -- many of whom were forced to join the cult as young boys. Given that the cult of Cybele was so popular in ancient Rome, I wonder if the tradition of castrati dates back to then in some form. Cybele is Neolithic in origin. At one point under Justinian the Apostate, Justinian tried to make Cybele a rival to Christianity and the Catholic church does have this habit of co-opting various pagan traditions.