I’d planned a different essay for this week, but since I posted my Cleopatra piece, the public backlash against Netflix and their ersatz “docu-drama” has reached histrionic proportions, so I changed course. Queen Cleopatra has been universally panned by critics and audiences alike. The casting of a Black actress in the title role has been roundly condemned by historians and outraged Egyptians, calling it cultural appropriation and racial insensitivity.

Personally, I’m thrilled that we can finally open a robust debate in mainstream culture about cross-racial casting: praising it when it succeeds, and rejecting it when it epically fails. Once effective, crying racism doesn’t seem to stifle dissent anymore. Audiences are starting to cry bullsh*t, demanding the right to love or loath these kinds of casting decisions at their discretion. Art can’t be ideologically gerrymandered. Folks are catching on to the way stories are being shoehorned into a Woke template. They can see the diversity checklist being ticked off, and when it distorts the truth, makes no sense, or preaches and patronizes, it’s the audience that’s getting ticked off.

Last year, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences introduced Representation and Inclusion Standards for Oscars eligibility in the Best Picture category “designed to encourage equitable representation on and off screen to better reflect the diverse global population.” Using a sort of “one from column A, two from column B” menu paradigm, filmmakers must meet certain quotas to be in the running for the top trophy. In the casting area, the requirements are as follows (from Oscars.org):

At least one of the lead actors or significant supporting actors is from an underrepresented racial or ethnic group in a specific country or territory of production.

This may include:

• African American / Black / African and/or Caribbean descent

• East Asian (including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Mongolian)

• Hispanic or Latina/e/o/x

• Indigenous Peoples (including Native American / Alaskan Native)

• Middle Eastern / North African

• Pacific Islander

• South Asian (including Bangladeshi, Bhutanese, Indian, Nepali, Pakistani, and Sri Lankan)

• Southeast Asian (including Burmese, Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Indonesian, Laotian, Malaysian, Mien, Singaporean, Thai, and Vietnamese)

In the General Ensemble cast:

At least 30% of all actors in secondary and more minor roles are from at least two underrepresented groups, which may include:

• Women

• Racial or ethnic group

• LGBTQ+

• People with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing.

—Now, here comes the most problematic one, in my view, which affects which stories we can tell:

The main storyline(s), theme or narrative of the film is centered on an underrepresented group(s).

• Women

• Racial or ethnic group

• LGBTQ+

• People with cognitive or physical disabilities, or who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Um… okay, let me see if I’m getting this right. In order for a film to be eligible for a Best Picture Oscar, the story has to be about women, or focus on race, or LGBT people, or center on disability. Well…that’s not limiting at all.

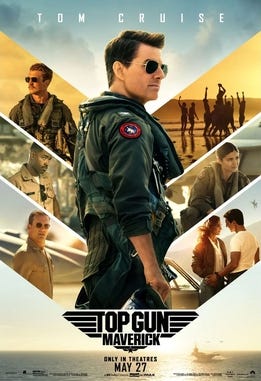

These diversity requirements don’t kick in until next year, and it will be interesting to see how it all plays out. I just find it fascinating that the top grossing movie of 2022 was Top Gun: Maverick, which met none of these standards, and was nominated for Best Picture. Just as fascinating, the next highest grossing film of the year was Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, earning about half what Top Gun made, but still in the hundreds of millions, but didn’t make the Best Picture nominations list. In fact, the two most popular films in America managed only one Oscar each: Black Panther for costume design, and Top Gun for sound design. Still, audience tastes were clear: they wanted action, special effects, lots of beat ‘em up and shoot ‘em up escapism. And they were happy to pay to see it played out by mostly white actors on the one hand, and mostly Black on the other. The diverse movie going public just wanted to be entertained. But leave it to Hollywood to ignore what the public wants to see. What do they know, those little people out there in the dark?

It’s no surprise that Hollywood’s elites have gone full Woke, or that the Academy—comprised of Hollywood’s elites—has decided to subject filmmaking to the DEI treatment, reserving the top honors and golden goodies for movies that preach the gospel. It’s rare that the Academy Awards reflect popular taste and enthusiasm. They were invented nearly a century ago by Hollywood to reward Hollywood and promote Hollywood, and politics and propaganda have always been in the mix.

But did the long years of the Production Code teach Hollywood nothing? The Code, sometimes referred to as the Hays Code, imposed upon the industry by the industry, under pressure from conservative religious forces, presented a whitewashed view of America for over three decades. With anti-miscegenation laws on the books in most states until 1968, all stories depicting interracial love, for example, employed white actors in blackface or yellowface, mostly with results that are appalling today, even for the diehard classic cinephile like myself. Historical films were not immune from these practices; perhaps the most egregious example is the casting of John Wayne as Genghis Khan in The Conqueror (1956). In fake eyelids and Fu Manchu mustache, the Duke makes you wanna puke.

The Code perpetuated stereotypes, marginalized people of color, utterly erased gays, and gave us three kinds of women: whores, virgins, and mothers. We’ve been coming back from it since the ‘60s, and so much progress has been made. So why would we now impose similar restrictions in the reverse? Is this some sort of weird cinematic reparations scheme? And how can these sorts of imposed artistic regulations—from the stories we tell, to who tells them and who enacts them—prove anything but false, manipulative and creatively stifling? The Queen Cleopatra controversy is just the beginning of what I predict will be a divisive and commercially disastrous trend of racial and ethnic backlash.

Why would we, in a time celebrating diversity, adopt such regressive practices? Not all stories worth telling would work with these diverse casting checklists imposed upon them. And so what? Aren’t there Black stories? Asian stories? And for that matter, what’s wrong with the occasional White story? Can’t we make enough movies to represent all kinds of people? After all, to quote Robert Palmer: it takes every kinda people to make what life’s about, yeah.

I recently attended a performance of Tom Stoppard’s play, Leopoldstadt, on Broadway. The story of two generations of a German Jewish family devastated by the Holocaust and the Cold War, it’s a poignant tribute from Stoppard to his Jewish ancestors. As the performance progressed, I noticed I was noticing something: the entire cast was white. This was absolutely appropriate, since the play was about white people, yet it was telling that I was surprised to see white people portraying them. I can’t deny that the authenticity was refreshing. The casting honored the real people who lived those experiences. But, under the new guidelines, if Mr. Stoppard’s moving play were to be made into a film—one worthy of the Academy’s top prize—this authenticity would, by fiat, be compromised, and non-white actors inserted into the cast. Aside from providing those actors employment, and serving a Woke political agenda, how would this serve the story? Where would be the sensitivity to those of us descended from European Jews, who see our own history in Stoppard’s saga? It reminds me of the scandal several years ago, when the Mormon church tried to posthumously convert Anne Frank. As my people say, such a thing would be a shonda: a disgrace.

I’ve been fortunate to perform the delicious role of “Uncle” Max Detweiler in two productions of the Rodgers and Hammerstein classic, The Sound of Music. It’s based on the true story of a musically gifted Austrian family escaping the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s. In the first production I did, we had an historically accurate all white cast. This was a decade ago, and not surprisingly, the use of authentic casting went unchallenged. After all, it’s a story about white people. My second experience of the show, in 2019, was in a small regional theatre in Vermont. This time, the cast was racially diverse. We had a splendid Black operatic soprano playing the Mother Abbess, and the seven Von Trapp children were a mix: Black, White, Asian, other. The reason for this was that the kids were cast from the local community, and the theatre prioritized, rightly, talent and ability. They cast the best kids they could find. The audience accepted this diverse vision and the show was enormously well received. The Sound of Music these days is often cast in non-traditional ways. Paper Mill Playhouse recently featured actress of color Ashley Blanchet as Maria. You might recall the television production of the musical starring Carrie Underwood, which featured the sublime Audra McDonald as the Mother Abbess. As I recall, people took more issue with Ms. Underwood’s country twang than with Ms. McDonald’s race.

So, what am I saying? I’m saying that diversity casting can work, but there’s nothing racist or white supremacist in casting a piece based on historical events about white people in an authentic way—with white actors. Imagine if these standards were imposed in reverse? Can you imagine white actresses playing Deena Jones and Effie White in Dreamgirls? If anyone tried that, aside from making no sense, it would be deeply offensive, and I am telling you—I would not be going.

I’m torn on some of this. I like the idea, in theory, of giving Hollywood an incentive to cast more people that aren’t cast enough, and tell stories about people whose stories don’t get told enough.

But will the beneficiaries of these adjustments want to see these films? Will other people not want to? I guess we shall see.

I don’t see many current movies, and I’m not really the target audience of most that are made. Will this change that? I’m skeptical that new types of movies will be made. It seems more likely that they’ll try to make the same kinds of movies but with these adjustments. It will be nonwhite actors and women actors dispensing the scattergun wisecracks and blowing bad guys (bad gals) away. Or the trite romcoms will be less white. Or the people in ridiculous suits against CGI backdrops would be less white and less male.

All of that would be to the good, but I still wouldn’t be seeing these movies.

Or, they may often make the exact same movies and figure “we aren’t making an Oscar-winning picture here. We are selling tickets.”

The overriding question for me is: do movies that don’t do all the things these new rules say they ought to do make those creative decisions because the filmmakers have a racist/sexist agenda, or because the audience wants to see what it wants to see? If there are really is an agenda behind the movies that don’t satisfy equity demands, then these solutions may fix a real problem. But I wonder.

It’s hard for me to believe that corporate attempts to do the right thing will continue even if it appears that revenue is lost as a result. If it turns out that better movies are made, and the public is happy about the change, that will be a nice thing. I’m just skeptical.

I like the idea of diversity and equity. But I suspect that forcing it on artists will sometimes lead to perversity and kitsch, just as the racist and sexist restrictive policies of old did.

I can comment on one specfic issue with the Academy's DEI requirements. They allow people to self-identify as "indigenous," and don't require that somebody be an officially-recognized tribal member. In other words, there are quite a few Elizabeth Warren-esque pretend Indians roaming in Hollywood.