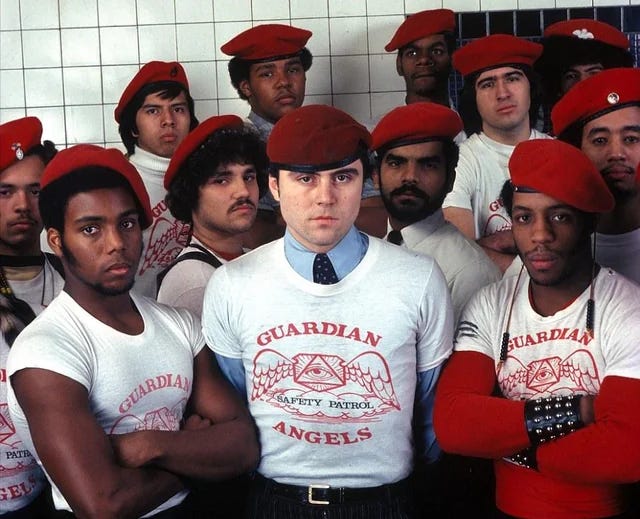

I’ve lived in New York City more than half my life. I first moved there in the late eighties, after graduating college, to pursue my acting career. My first “day job” was at Bells Are Ringing, an answering service for the theatrical profession, where I sat in a cubicle, chain smoking, and took messages for the stars of the future. The service was located in the basement of a building adjacent to The Port Authority (42nd Street and Eighth Avenue), where I would catch the A train at midnight after my shift to make the trek uptown to my airless sublet at 200th Street and Dyckman, at the top of Manhattan. I don’t know if you’ve seen photos of the subway at that time: overcrowded, covered in filth and graffiti, occupied by every kind of crazy. For wide-eyed, twenty-one year old me from the Boston suburbs, that long train ride every night was intimidating. But I always breathed a little easier when members of the Guardian Angels would step onto my subway car. These unarmed, crime prevention volunteers were young men of every color and background who had trained in basic martial arts, first aid and CPR. Their very presence—in their red berets and jackets—signaled to New Yorkers that someone was looking out for them, and let pickpockets, muggers, and other would-be criminals know they were being watched.

Over three decades living in New York City, I’ve seen it all on the subway. I’ve seen people urinate and defecate openly on trains. I’ve witnessed people copulating, masturbating; I’ve seen women being groped by perverts taking advantage of the crowd to cop a feel. I’ve had my pocket picked. I’ve seen fistfights, drug deals, junkies shooting up, and every manner of loud, belligerent and deranged behavior from mentally ill and out of control people terrorizing riders just trying to get from A to B in one piece.

Today, the subways are designed to be tourist friendly spaces (at least, in tourist heavy areas): clean, gleaming train cars with no graffiti; platforms and subway entrances embellished with expensive “art installations” in mosaics and sculpture. But even in tourist friendly stations and on train cars in general, since the pandemic, there’s been a plentiful lack of police presence and security of any kind. We no longer have Guardian Angels. And, with automated fare card dispensers and electronic turnstiles, most stations no longer have any human attendants working in them; no human supervision at all times of the day. While there’ve been cosmetic upgrades to trains and stations, the crazy and criminal elements have been given free rein underground in my city.

You know where I’m going with this. I think what happened to Jordan Neely is a tragedy. This young man, afflicted with mental illness, heavily addicted, homeless and disconnected from his family, was arrested forty-four times for an array of offenses. Yet he was returned to the streets and the subways again and again. This cycle, the result of systems that failed both to help Neely and to protect the public from him, inevitably led to tragedy; it was inevitable that harm of some kind would come, for him and those around him. But a system didn’t get on that train and start menacing passengers. A system didn’t threaten to kill people on that subway car.

I’ve been on the subway with unhinged people like Jordan Neely. I’ve felt the fear of being trapped in a closed space with a raging lunatic, not knowing what might happen. If I had been on the train the day that Daniel Penny stepped up and attempted to subdue Neely, I’d have been as grateful to him as many of the witnesses who testified at his trial were. I’m not going to argue the details of the encounter, or the force Penny used, or the length of time he held Neely in restraint. I’m not going to go there—because I wasn’t there, and neither were you. The result of those six minutes was a tragedy: for Neely, for Penny, for our city, and for the culture at large. This case has been politicized and racialized, framed as another George Floyd incident, and exploited by BLM activists, who continue to call it a “lynching,” labeling Daniel Penny as a racist and white supremacist. But, Penny has been acquitted by a New York jury of his peers—half of them people of color—and whether or not one agrees with the verdict, due process has been done. Had Daniel Penny acted out of racism or a callous disregard for Neely’s black life, it would have come out at trial, and I for one don’t believe he did. Had the deranged and tragic individual who terrorized those men, women and children on the subway that day been a white man, I believe Penny would still have followed his instincts and intervened. But we wouldn’t know his name. It would never have become a national story. We can, and should, have the urgent conversation about our spiraling homelessness, mental illness and drug addiction issues in cities like New York, San Francisco and in our country at large. But in this particular case, I believe justice was done. I hope Penny can pick up the pieces and move on. I hope, too, that Neely’s family will heal from this tragedy and that they might look within—what might they have done to keep Jordan off the streets, and placed where he might have been helped and kept safe? There can be no real resolution here—only recovery. As Oscar Wilde wrote, “The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”

As a New Yorker, I’ve been horrified and alarmed by the disintegration of the social fabric of my city in the past four years. It’s telling to me, that as all of us were trapped in our apartments during covid lockdown, building construction boomed. From our isolation we watched tall, gleaming, glass and steel apartment towers going up all around us in my Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. Developers and contractors were creating a glossy cityscape—as the rot underneath festered.

During that time, ostensibly to prevent overflow in shelters and prisons, and slow the spread of infection, hundreds, if not thousands, of people were brought to midtown Manhattan and dumped. Many of these individuals were mentally ill, addicted to street drugs, aggressive and violent. In April of 2020, The New York City Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice released nearly 1,500 prison inmates early, placing them in “reintegration hotels,” run by non-profit ATI (Alternatives To Incarceration) organizations. One such hotel was the Skyline, just four blocks from where I live. Inmates from Riker’s were put there under what we were assured were safe conditions: those on parole had a posted curfew, and were, we were told, regularly assessed by mental health professionals and drug abuse counselors and that there was always some sort of security or staff supervision. What I and my neighbors witnessed during that time was an influx of unstable people, who may have been safe from the spread of covid at Riker’s prison, but who made Hell’s Kitchen residents’ lives decidedly unsafe.

I spent six months during the worst of lockdown in my one bedroom apartment, caregiving for my 83 year-old mother, who had dementia. We would take a walk through the neighborhood early every morning to get some air and stretch our legs. One day, we passed a building with scaffolding out front. Under the scaffolding, on a broken down sofa, a foot or so from the public sidewalk, two people were mainlining drugs in broad daylight. One was bleeding openly from numerous attempts to find a vein with his syringe. Concerned, I called 3-1-1, a non-emergency hotline in the city which provides services for various issues, including those related to the homeless. The person who answered my call asked me, “Did you talk to these people?” I replied, um, no, I’m here with my elderly mother. I am just concerned that there’s some public health risk here. “Did they seem okay? Is there a medical emergency?” I remarked that the reason I called 3-1-1 was so that someone professional might assess that, and perhaps offer these people some help. The blasé hotline operator displayed no urgency, but said they’d send someone to check in on the junkies. Never was I asked if I or my mother was okay. I shouldn’t have bothered.

A few months later, I was running some errands in the neighborhood. I had some large grocery bags over my arm as I stopped at the little newsstand on my block to use the ATM. Outside the door of the newsstand, a very large, agitated and obviously mentally disturbed man was standing, yelling at a broken cell phone incoherently. I carefully pulled the door open, and as I was going inside, one of my bags slightly brushed this man’s arm. He went ballistic, and began screaming at me through the door of the newsstand. “Come out here, you fucking faggot! I’ll fucking kill you!” Inside the newsstand, it was just me and the small, elderly Pakistani man behind the counter. Rattled, I got my cash from the ATM, but it became clear that I was not going to be able to get out of there without being confronted, and perhaps assaulted, by the deranged man outside, who was almost a foot taller than either me or the newsstand guy, and at least a hundred pounds heavier. I told the counter man that I was going to call the cops. He begged me not to. He somehow found the wherewithal to go out and calmly managed to get the lunatic to back up a yard or so from the door, allowing me to slip out and literally run down the block to my building. The howls of “Fucking faggot!!” rang out behind me. I can still hear them.

When I reached my apartment, I was shattered. In three decades of living in that neighborhood I’d never been accosted like this, nor had I ever been gay bashed or been subject to homophobic abuse. I went on Facebook and posted about the incident, relating what had happened and how terrifying it was. I mentioned that I had almost called law enforcement, adding, with some understandable emotion, that I didn’t want to be told anymore that we don’t need police (the Defund the Police movement was then at fever pitch). Most comments were concerned and horrified. But some were gobsmacking, scolding screeds about “privilege.” This one shocked me the most:

Why would a cop have been more beneficial to you? I’m just speaking from experience and from the experience of my black friends’ encounters with law enforcement. If you were black would you have wanted to call the cops? Even if you were the victim you would potentially be in danger just for the color of your skin. Wanting police to make us feel safe is definitely a runoff of our white privilege.

WHAT?? I couldn’t believe it. Minutes before posting my account, I was being harassed with homophobic slurs and threatened with death by an unhinged man three times my size a block away from my home. What should I have done? Confronted this guy? Taken the beating because… “white privilege?” I couldn’t fathom the total lack of empathy; the unbelievable insensitivity. Even if this so-called Facebook “friend” wanted to make some political point about race and the police, was this really the moment?? Obviously, this person was not a friend. He was a white gay man of my age, and yet he couldn’t put himself in my shoes—he claimed his own “lived experience” and preferred to virtue signal and shame me for thinking the NYPD might be needed to protect me from harm. It is these same armchair social justice “warriors” who think it’s okay for packs of shoplifters to rip through NYC stores, looting whatever they can get their hands on because…poor brown people? To this day, I have to ask a store associate to unlock the toothpaste for me at my corner CVS. This is progress? I gotta tell you, in the mid-nineties—when I was on a first name basis with the hookers who worked my corner; when I got my pocket picked grabbing a coffee at the donut shop; when 42nd Street was a boarded up wasteland of dead sex shops and crumbling old theaters (before Rudy Giuliani and Disney turned it into a tourist theme park)—back then, I felt safer to go about my life than I do now.

Last November, on a sunny Friday in the middle of the day, in the middle of Times Square, I was assaulted by a random crazy man who punched me in the face and called me an antisemitic slur. I related this story in an earlier post here. Not only had I never been physically assaulted in New York, I had never been physically assaulted. I guess my “white privilege” had prevented it before then, and my “number was up” or something, but I was shattered, not just by the assault, but by the skepticism and lecturing I received on social media, much of it of the tenor of my “friend” from the newsstand incident. I was hectored about not having reported the assault to police. Maybe it was caught on CCTV? At least there’d be a record of what happened. The insinuation was that because I hadn’t reported the incident that I was lying about it for some racist reason of my own. So…when the crazy giant at the newsstand was screaming he’d rip my faggot head off, my impulse to call 4-1-1 was “white privilege,” but when I actually got punched in the face by a belligerent, unhinged person of color in broad daylight—now I was supposed to report it to the cops? What would have been the point? Nothing would have been done about it, and had my attacker actually been apprehended, I’d have been accused by SJWs—“fighting the good fight” from their L-shaped sofas on social media—of exerting my “privilege.”

There’s a real problem going on in our society, especially in cities like New York, where ideologues and activists, who are making some serious bank off of social and racial strife, are influencing public policy and making our streets and neighborhoods unsafe. Their misguided ideas prioritize the rights and needs of dangerous and disruptive individuals over those of law abiding citizens. The loudest voices amongst the “progressives” pushing these policies, who reside in NYC, live in another city from the one I live in. They view Manhattan from their luxury high-rise apartments. They never take the subway. They don’t shop at CVS or Target. It must be nice to lecture the rest of us on our “privilege” from such elite urban aeries. Such people are the types who are currently lionizing the alleged CEO assassin, Luigi Mangione (and his amazing abs). Stalking a man on the streets of my city, just blocks from where I live, and shooting him in the back in cold blood, was apparently an act of heroism—because…health insurance companies are evil…? What if a bystander had wandered into the line of fire that night and was taken out along with Brian Thompson? Would he or she have been mere collateral damage in the fight for socialized medicine? Do these ideological idiots think they get to decide who deserves to die, and who doesn’t? Are we really going to condone—or worse—celebrate this kind of vigilante violence on our streets? Well, buckle up folks. It’s the Wild West.

Some people in this country, who’ve never been to my city, consider New York a cesspool of filth and depravity and can’t fathom why people like me would make it home. We have only ourselves to blame if harm and hardship come our way. Despite all I’ve related here, I would say that New York City is still the greatest city on earth. New York City has survived far worse than what we’ve seen since the pandemic—and we will survive this, but policies and politicians need changing (starting with Mayor Eric Adams). I was in the city on 9/11. I’ve seen how New Yorkers come together in times of crisis and I’ve been inspired by our resilience and resolve. One of my heroes, James Baldwin, wrote: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” I feel the same about New York.

I love the city—even when it’s letting me down—because New York has taken care of this poor, struggling artist in so many ways, over many years. I live in the granddaddy of affordable housing for performing artists—the poster child for Housing and Urban Development—Manhattan Plaza. This complex of two hi-rise apartment buildings in the heart of the theatre district was converted to affordable housing in 1970, at a time when my neighborhood was a gang war zone, and the project played a major role in cleaning up and reviving midtown—positive effects we still see today. You can learn more about Manhattan Plaza by watching the astonishing documentary The Miracle on 42nd Street. Living in Section 8 housing, in a diverse and artistic community that takes care of the most vulnerable, has made my career and my life in NYC possible. New York non-profit organizations have provided me with pro bono legal assistance, and helped me navigate the healthcare marketplace when I went on Medicaid. I’ve received incredible support from GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis) since my HIV diagnosis, including counseling, nutritional resources, and other services. The Entertainment Community Fund (formerly The Actor’s Fund), a charity for the performing arts, has provided me with career counseling and emergency funds, and they saved both my life and my mother’s, when the good people there helped us get Mom into The Actor’s Fund Home, at the height of the pandemic, where she lived out the remaining months of her life under their excellent care. New York, at its best, takes care of its own. New York, at its best, prioritizes New Yorkers and helps lower income and other vulnerable residents to live more safely and with dignity.

The system did fail Jordan Neely. Many systems, no doubt, failed him. He was arrested dozens of times. He kidnapped a seven year old. He broke the face of an innocent elderly woman in a public space. So, why was he still out on the streets and on the subways, where he posed a threat to himself and others? Where was his family? Seems to me, despite their wails of grief and cries of injustice now, they failed Neely too—long before he encountered Daniel Penny on that fateful day. Why wasn’t he in a facility where he could be treated for his mental health issues and addiction, and kept where he couldn’t endanger the public? Daniel Penny made a decision in a split second on that subway train, when Neely was menacing men, women and children of all races, threatening to kill someone. He stepped in to protect those people, and his actions no doubt contributed to the tragic, accidental death of Jordan Neely. But Neely’s own actions contributed to his tragic end as well.

I’ve seen comments online from people musing about what they might have done had they been in Penny’s shoes. I am confident that the answer is nothing. I wouldn’t have gone anywhere near Jordan Neely, and would have jumped off that train at the first possible opportunity. Daniel Penny didn’t subdue Neely that day because he saw a black man and decided to “lynch” him. He saw a deranged and potentially violent man and he took action to prevent harm. Wouldn’t an MTA cop have done the same, had one been present (as they so rarely are these days)? Wouldn’t one of the Guardian Angels have done something similar back in the day? Daniel Penny did something I, and most New Yorkers, would never have attempted, at great personal risk, and despite his acquittal by a NYC jury, he’s still being vilified by the activist class and the race grifters who want to exploit another white-on-black violence story on which to raise millions once again.

Here’s the real tragedy. The next time a Jordan Neely comes barging onto a subway train and starts threatening to kill passengers, there won’t be a Daniel Penny to stop him. Even if a brave person has the thought of stepping in to intervene, such a person will now walk away, rather than face what Penny continues to deal with, despite his innocence, and—in my opinion—heroism.

To a slightly lesser degree we have the same thing going on in the UK. With the same lack of policing, lack of interest and similar progressives who live lives sheltered from the realities of the things they call for and the concerns of the people who endure this that they dismiss.

Wow. Articulate as always and so profound.