I’ve struggled to complete this piece. I started it at the end of June, originally intending it as a tribute to one of my heroes, John Adams; something to post on the Fourth of July. Then the world erupted in mania following the troubling Presidential debate. Earlier in the month, it seemed Juneteenth couldn’t be celebrated without angry indictments of the founding and calls to abolish Independence Day. The forthcoming election had pundits and commentators on all sides “chicken littling” about the catastrophe that loomed, whichever geriatric we elected. Pro-Hamas protestors in our cities crying, “Death to America,” literally collided with Pride paraders and kink exhibitionists chanting “we’re coming for your children.” Woo. Bring on the fireworks.

Then…an assassination attempt. Followed swiftly by a maelstrom of spin and insinuation…absurd histrionics and conspiracy theorizing on one side; unhinged religious prognostication on the other. Then President Biden dropped out of the race, passing the torch to V.P. Harris. More maelstrom: accusations of racism and sexism, melodramatic speculation about coups and election stealing. Everyone, on every side, of every stripe, and with every motive, has shown their true colors—and the view ain’t pretty.

Why has this essay taken me so many weeks to compose? I’ve spent nearly that entire time thinking deeply about what it means to me to be an American.

I turned eleven in 1976: the year of the United States Bicentennial. Everything everywhere was red, white and blue. My family went to see the Bicentennial Ice Capades at the Boston Garden, starring Olympic Gold Medalist Dorothy Hamill. We gorged on Americana. Of course, growing up in the greater Boston area, the American Revolution was all around me. We took school field trips to walk The Freedom Trail and visit Paul Revere’s House. We read Johnny Tremain, and tossed fake tea chests into the harbor off the Boston Tea Party Ship. My own paternal ancestors were 17th century Massachusetts Bay colonists.

The year after the Bicentennial, the entire nation gathered around their television sets to watch the groundbreaking mini-series based on Alex Haley’s best selling novel, Roots. The show had a powerful impact on me at that tender age, and inspired me to educate myself more deeply on the evil history of slavery in America. My adopted sister Clea was black, and my mother always sought out books, films and cultural events that might bring her closer to her racial ancestry—something that enriched me and my brother at the same time. I grew up with a sense of reverence for history, especially American history, and I’ve always been in awe of the Founders, and what they achieved, against impossible odds, in the establishment of our country.

In 2009, I had my first audition for the role of John Adams in the musical 1776. I didn’t get it. But preparing for that audition inspired a determination in me to play this guy. I mean—I basically was Adams: a short, explosive little know-it-all from Massachusetts! I relentlessly pursued the part, auditioning for twelve different productions until I finally got to play him, at the legendary Cape Playhouse, in 2014. Obsessed as I was with the role, and Adams himself, I immersed myself in a comprehensive study of his life, times, the role he played in the War of Independence and the founding of the United States, and his service as the second President. I inhaled the wonderful miniseries based on David McCullough’s definitive biography, starring Paul Giamatti. I read all the volumes of Adams’ autobiography and his diaries. I visited Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and met with the archivists at the Massachusetts Historical Society, where I wangled a private viewing of actual Adams letters, including the ones to his wife, Abigail, and his personal, handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence. I visited his birthplace in Braintree and his house in Quincy. In other words, I geeked out! I even did a homemade video blog in twelve parts, chronicling my research, rehearsal and performance in 1776.

I find myself often indignant about the way our history is being framed, distorted and often, from sheer ignorance, simply made up to suit a specific narrative with one goal: branding the United States a racist, genocidal and evil project conceived by white men in order to perpetuate slavery and the subjugation and oppression of non-white people. The 1619 Project places the founding of this country at the moment when British boots touched the soil of Virginia, establishing the plantations that brought genocide to Indigenous people and the evil dehumanization of the human beings that were brought here in chains. The British privateers who established Virginia were doing what Britain did for centuries: invade a distant country, disrupt the culture, seize the land and resources, and send the booty home. Empire. Virginians were British loyalists, in this new land claimed as British soil.

Fast forward 150 years. Five hundred miles north of Virginia, in the town of Braintree, Massachusetts, John Adams is born, a farmer’s son; indeed, Adams would remain a farmer for the rest of his life. Massachusetts Bay Colony was his country; he had as much conception of Virginia as he did of England. While he and his family paid taxes as subjects of the English King, Adams didn’t think of himself as an Englishman, growing up with full awareness that the culture he was born into was a culture of indentured servitude. He and the people in his community paid crushing taxes to the Crown, yet were denied the rights and protections of British citizens, with no representation in government, utterly dependent on England for the importation of essential goods and resources. The colonists were forbidden access to arms and denied the formation of a militia of any kind. Talk about apartheid.

This is the crux of my objection to framings like The 1619 Project: the entire actual war that was fought is entirely glossed over. An enormous gamble, against all possible odds; a war for freedom against tyranny. An act of treason through resistance; a costly struggle to establish a new nation. John Adams, born, bred and educated in Massachusetts Bay Colony, had never traveled farther than Maine when he arrived in Philadelphia to join the First Continental Congress. It might as well have been Paris. Imagine the culture clash when Adams encountered Virginians and South Carolinians, whose totally alien civilization, 500 miles from Braintree, was prosperous, decadent, and thoroughly British. Of course, we know that it was the issue of slavery upon which the achievement of the Declaration ultimately hung. Peter Stone, in his book for 1776, captures this horrible moral impasse between North and South eloquently.

Adams, of course, was a lifelong abolitionist, as was his incredible wife and partner, Abigail, who reminded Adams often of the hypocrisy of fighting for their own freedom whilst allowing fellow human beings to remain in bondage:

I wish most sincerely there was not a Slave in the province. It allways appeard a most iniquitious Scheme to me-fight ourselfs for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have. You know my mind upon this Subject. ~ Abigail Adams to John Adams, September 22, 1774

One of the most moving scenes I had to play as Adams was the climactic moment where Rutledge, of South Carolina, presents his ultimatum: strike the anti-slavery clause from the Declaration, or the South walks, ending the American project.

John: Mark me, Franklin, if we give in on this issue, posterity will never forgive us.

Franklin: That’s probably true. But we won’t hear a thing, John—we’ll be long gone. And besides, what will posterity think we were—demigods? We’re men—no more, no less—trying to get a nation started against greater odds than a more generous God would have allowed. John, first things first! Independence! America! For if we don’t secure that, what difference will the rest make?

They were men. They were human beings, flawed, struggling, living in dangerous circumstances and in physical conditions none of us could even fathom today, let alone endure. And they failed to stamp out the evil of slavery, consigning generations to untold horrors and dehumanization, and the scourge of a hideous civil war that nearly destroyed the union for good and all. Still, America stumbled forward, failing, striving.

Oh yes, about those 17th century Massachusetts Bay colonists I’m descended from…

Actually my ancestors on both sides came to these shores to escape religious persecution. Twelve year-old Gamaliel Beaman sailed from England to join his Protestant older brothers in Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1659. He would grow up to become one of the founders of the town of Lancaster, which was razed to the ground when Indian tribal mercenaries in the pay of Catholic forces to the north descended upon the settlement. Gamaliel and his fellows rebuilt. One of his 19th century descendants would marry Joseph Smith and establish the Church of Latter Day Saints with him. History is always a mind-blower.

My maternal great grandmother, Genya Prizant, survived the Kishinev pogroms and fled to America in 1903 at the age of fifteen. I chronicled her journey in another essay; it’s a story of steely determination, strength and ingenuity. I was raised Jewish and I identify (lord, I am sick of that word) as such. I’m a Jew, connected to an ancient bloodline, and the son of brave and brilliant survivors. I’m also a descendant of original Massachusetts Bay colonists, and often feel a sense of awe at how deep my American roots go. My ancestors endured unimaginable hardship and struggle; wars, turbulent political and cultural upheavals. I’m American because they came here to be free.

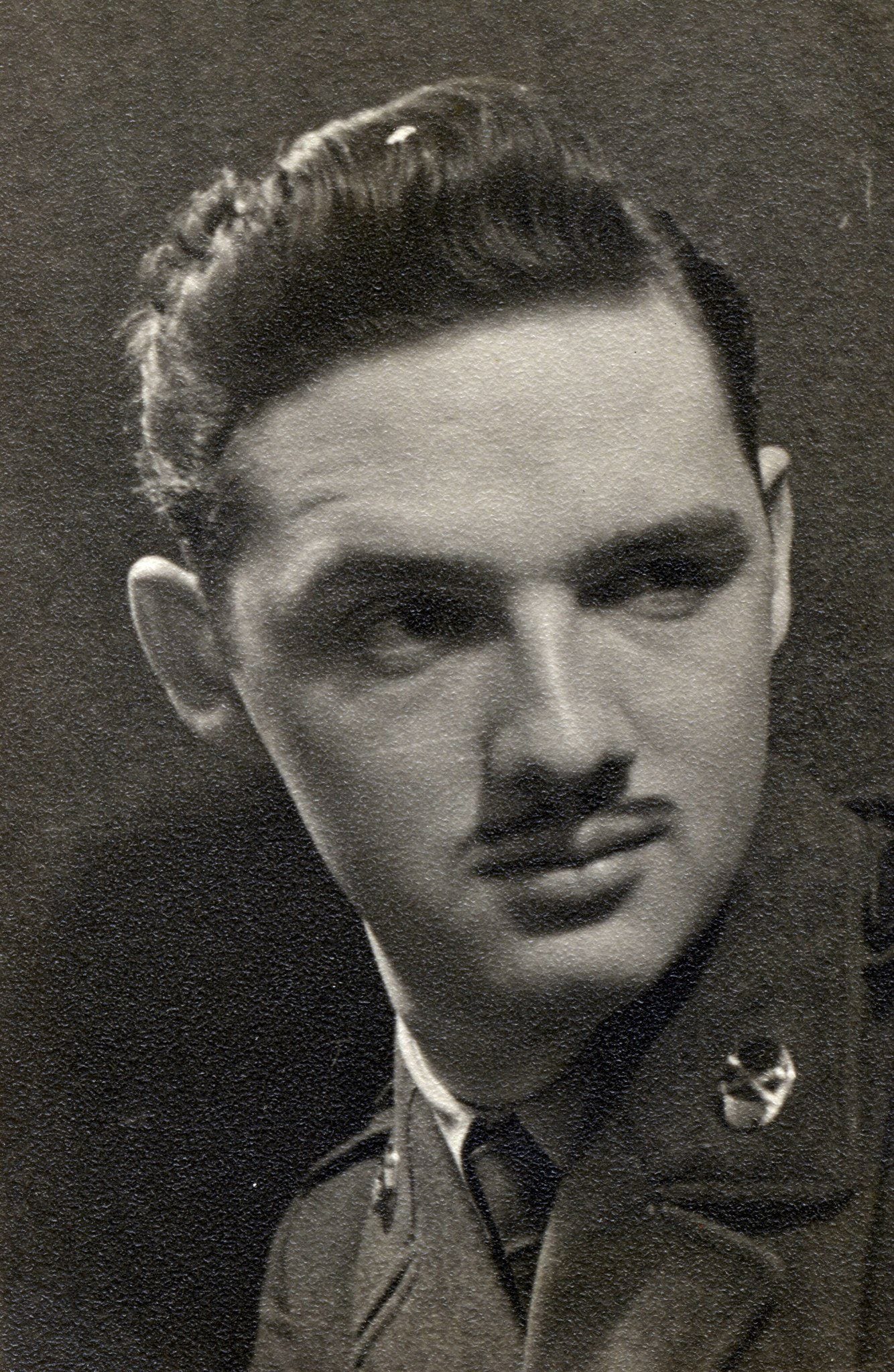

My father grew up the eldest of seven on a farm in upstate New York during the Depression. He and his siblings were educated in the same one room schoolhouse. Dad enlisted at seventeen, and served in the Korean War. Via the G.I. Bill, he attended college and graduate school, eventually becoming a professor. My mother, a first generation American, was the first woman in her family to graduate college. Because of my parents, and because I was born American, I’ve been free to pursue the life and work of my choice. As a gay man, and as a Jew, I’ve experienced discrimination and hatefulness. I’ve fought for the right to be openly who I am, aware that it’s a fight that was being fought before me, by those who paid a higher price than (I hope) I ever will. I’ve seen our nation grapple with civil rights and equality and make enormous strides.

I was overwhelmed with incredulity and revulsion as I watched the video of the recent Pro-Hamas protest outside Union Station in Washington, DC. The tearing down and burning of the American flag was hard to watch, but it always is, and it’s been a popular symbol of protest for decades. When I saw people gleefully taking video of the burning stars and stripes with their smartphones, I reminded myself what the First Amendment is about and the challenge it presents. Aaron Sorkin, in his excellent screenplay, The American President, gives these words to his fictional President Shepherd to say:

America isn't easy. America is advanced citizenship. You've gotta want it bad, 'cause it's gonna put up a fight. It's gonna say, "You want free speech? Let's see you acknowledge a man whose words make your blood boil, who's standing center stage and advocating at the top of his lungs that which you would spend a lifetime opposing at the top of yours." You want to claim this land as the land of the free? Then the symbol of your country cannot just be a flag. The symbol also has to be one of its citizens exercising his right to burn that flag in protest. Now show me that, defend that, celebrate that in your classrooms. Then you can stand up and sing about the land of the free. —Aaron Sorkin, “The American President”

You know what made my blood boil about the Union Station protest? Not the burning of our flag, but the raising of the flag of terrorists and butchers, of a “brotherhood” that seeks not just the annihilation of the Jews, but of America. No. You can burn the flag in protest, but you don’t replace our flag, in our nation’s capital, with any other flag. That really rankled. I was rather chuffed to hear Netanyahu acknowledge those North Carolina guys. It’s interesting to read Sorkin’s words, written in 1995, as the words of an imagined Democrat President, and to realize that, today, freedom of speech is looked upon as a right wing value, and to some, the flying of the American flag is evidence of fascism, not patriotism.

But screw that. I am blessed to be an American. I’m descended from colonists and refugees, from Protestants, Mormons, Jews. I’ve no doubt they were all flawed, full of faults, human. Oscar Wilde wrote, “The truth is rarely pure, and never simple.” We will never truly, definitively, know everything that happened throughout history and why. But we see the results of it all in our lives today, for good as well as ill. The assessment of the critical justice zealots is that we must dismantle, rewrite, even erase our history in order to undo all that our horrible, racist, genocidal forbears created. They don’t seem to realize that if we do that, we undo ourselves.

The preservation of American ideals is essential to our survival as a country and must not be dismantled or erased. We must reach for them, even though we may fail, again and again. Another of my heroes, and one of the great Americans, James Baldwin, wrote: “I love America more than any other country in the world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” We must criticize. We must question, and debate, and listen to all voices. We must also vote, contribute, speak out, and volunteer. We must hold ourselves, as citizens of this country, responsible for its preservation and survival. We are, after all, The People. Advanced citizenship.

John Adams, writing to Abigail, remarked, “I must study Politics and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematics and Philosophy.” In another letter to his son John Quincy, after urging him to attend to his serious studies, adds a suggestion: that he carry a slim volume of verse with him at all times. “You’re never alone with a poet in your pocket.” Adams was passionate about scholarship and achievement, but he had a beating heart; he believed in love, in honor, in reaching for ideals even when failure seems inevitable.

In a recent speech, Konstantin Kisin, author of An Immigrant’s Love Letter To the West, said something about his son’s future that reminded me of Adams own love and determination for his son:

The history of our civilization was not made by people who always got everything right. It was made by people who made mistakes too. It was made by people who dared to believe they could solve the problems they faced. The story of the West is the story of audacity.

There are some people, whose brains have been broken by an excess of education, who believe that our history’s evil; that we do not deserve to be great, we do not deserve to be powerful, that we must be punished for the sins of our ancestors. To them, the past is abominable, our present must be spent apologizing, and our future is managed decline. My message to those people is simple: how dare you? You will not steal my son’s dreams with your empty words.

I bet Mr. Kisin carries a poet in his pocket.

Thoroughly enjoyable.

As I think you know JA is also a big hero of mine.

I am currently reading Nathaniel Phillbrick's Bunker Hill which details the run up to that pivotal battle in MA.

What I find so interesting is the sheer level of political violence (including tarring and feathering) which happened. Burning flags is possibly better than pouring molten tar over suspected transgressors. But there are reasons why violent protest is unlawful as opposed to peaceful protest.

The American Revolution was not a sedate affair. It starts messy and gets even messier when you get to the Carolinas when the Wild Geese really start taking their revenge for being defeated in the Jacobite Rebellion.

The 1619 Project promised much but had many failings --including the failure to show tightening of the manumission laws (some of which were supposed to be protection i.e. you couldn't just free a slave who could not work -- the freedom to starve is not really freedom) and indeed the failure to consider the extent of the illegal importation of slaves after 1804 (a point which is often brushed under the carpet -- the last importation of illegally trafficked Africans was the Clothide in 1860 -- consider the growth in the enslaved population post 1804 when cotton growing really takes off and ask yourself where did all those people come from and if indeed certain Americans have always been willing to smuggle anything and everything to earn a buck)

America is not perfect but when you look around at other countries and their traditional way of doing business, you have to say that it is a huge beacon of hope. Its existence has changed and altered the world for the better.

Despite having lived in the UK since 1988 (and becoming a British citizen in 2018) I do at my core remain proudly an American.

I reblogged you on my stack Jaime!

This piece was excellent and captures the moment really well…

https://open.substack.com/pub/jennyhatch/p/james-beaman-on-being-an-american?r=87fg5&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Cheers!

Jen