This Land Was Their Land

Talking Land Acknowledgements with Indigenous Artist Melody Pilotte

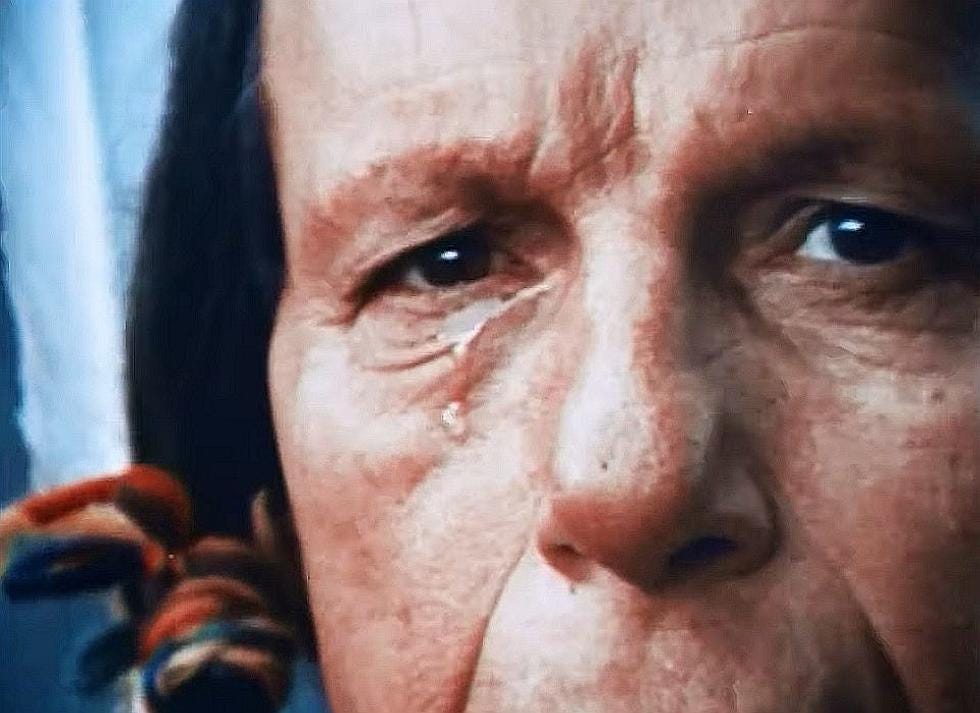

When I was a kid, there was a PSA on television that made me cry each time I saw it (I was, admittedly, a dramatic and sensitive child). It depicts a man in Native American garb—buckskins, braids—canoeing through polluted waters, surveying a landscape of litter and belching smokestacks, standing beside a crowded highway as a bag of trash is tossed from a car, landing at his feet. The man turns to the camera and locks eyes with us, a single tear falling down his cheek. The message was clear: we have desecrated the land sacred to Indigenous people. The ad was first aired on Earth Day, 1971, by Keep America Beautiful, an environmental protection organization.

I was surprised to learn, when preparing this essay, that the “Crying Indian” PSA was still on the air until about a year ago, when Keep America Beautiful announced they were retiring the spot and transferring the rights to the National Congress of American Indians Fund, admitting that it perpetuated stereotypes and misappropriated Native American culture.

This sin of cultural appropriation is personified by the “Crying Indian” himself: an actor who was known as Iron Eyes Cody. Cody was not Native American. Not even a little bit. He was born in Louisiana, the son of Italian immigrants, and his given name was Espera “Oscar” DeCorti. In the 1950s, when cowboys and Indians were all the rage on television, DeCorti changed his name, fashioned himself as a Native American, and arrived in Hollywood as Iron Eyes Cody. He worked for decades in film and TV, and lived his daily life under this assumed Indigenous identity. He even married a First Nations woman, an archaeologist of Seneca and Abenaki descent, with whom he adopted two sons, of Maricopa and Dakota extraction. Now, here’s where it gets weird.

Clearly, Cody lived a lie—a lie which, in today’s culture, would get him cancelled a thousand times over. He was a “Pretendian:” a term I’ve become more acquainted with since the Elizabeth Warren “Pocahontas” scandal. Cody pretended to be Native American and profited from the lie, becoming an icon of a culture to which he didn’t belong. He did use his fame to further Native American causes throughout his long life, and he was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1983. But most curious of all: despite being outed in the ‘90s by a journalist from his home state of Louisiana, who revealed his true ancestry (which Cody adamantly denied), he was honored by Hollywood’s Native American community for his contribution to film—as a “non-native.”

Wait…what??

In these times of identity politics and diversity/equity/inclusion, there still appears to be misinformation, controversy and lots of gray area around who is and who isn’t an Indigenous person in America. Hollywood, and the entertainment industry in general, have been tentative; tip-toeing somewhat around what qualifies as authentic representation of First Nations people. They’ve been slow in creating visibility and opportunity for Native American artists and storytellers. This is changing, thankfully, with films like Killers of the Flower Moon, and new streaming series like Echo. But what took so long? With the rise of Black Lives Matter four years ago, and the racial reckoning it promised, there’s been a huge surge in black representation in all areas of media. Yet, despite the coining of the term BIPOC (Black/Indigenous/People of Color) which clearly places Indigenous people second within the hierarchy of the racially oppressed, until recently the most we’ve seen done to address the issue of Indigenous representation is the somewhat empty gesture of the Land Acknowledgement.

Riding the wave of outrage following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, a collective of BIPOC theatre makers issued a manifesto entitled We See You White American Theatre. Among the many demands it makes, WSYWAT requires the adoption of the ritual Land Acknowledgement:

We demand the naming and acknowledgement of American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian tribal land and its Native peoples who have lived, currently live, and will live on the land where any theatre activity happens.

Land acknowledgement practice must be incorporated into first rehearsal rituals and at the beginning of any official meeting at Broadway, Off-Broadway, LORT, Educational and BIPOC theatres, because we all must honor tribal sovereignty and self-determination.

Acknowledge that American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians exchanged millions of acres of land through treaties for basic needs and rights despite the fact that every treaty was broken by the US government.

Practice ongoing acknowledgement of this mistreatment and the need to rectify the debt that American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians continue to pay for allowing others, including other displaced and removed Indigenous peoples, to be on their homelands.

Recognize that the "I" in BIPOC refers to all Indigenous peoples, which can be yet another erasure of the specificity of the 573 Tribal Nations who negotiated with the US government and have retained continuous traditions and folkways in the wake of genocide. Learn our tribal affiliations. Call us by our rightful names.

And now… enjoy 42nd Street!

Good god. No wonder theatre is withering nationwide. Is a theatre the place where historical wrongs are righted? Should theatre be an arena where its patrons are made to atone? We used to entertain, uplift, not evangelize and scold.

These ritual acknowledgements, now so ingrained in the protocol of theatre—rattled off tonelessly like a pre-flight safety demonstration before every curtain—what exactly do they achieve?

Graeme Wood, in his 2021 piece for The Atlantic, Land Acknowledgments Are Just Moral Exhibitionism, writes:

“A land acknowledgment is what you give when you have no intention of giving land. It is like a receipt provided by a highway robber, noting all the jewels and gold coins he has stolen. Maybe it will be useful for an insurance claim? Anyway, you are not getting your jewels back, but now you have documentation.”

In Canada, the practice of land acknowledgements predates the ascent of BLM and the wave of antiracist activism that came with it.

VICE’s 2019 story, Indigenous Artists Tell Us What They Think of Land Acknowledgements, features comments like these:

“Land Acknowledgements smell like condescending bullshit to me. Here's why: Attaching an Indigenous identity to the Land Acknowledgement deters the conversation from what we can all do together and instead to the commiseration of a lost culture. We are not lost. I don't want to think about that history every time I see a show and I don't want to listen to an apology from an artistic director who is not in any way responsible.”—Cliff Cardinal, poet

“It feels like many institutions are checking their box. It’s on their to-do list, which negates the point completely. Name the nations, but also say what your relationship is to the land you’re on. What’s the history?” —Yolanda Bonnell, actor

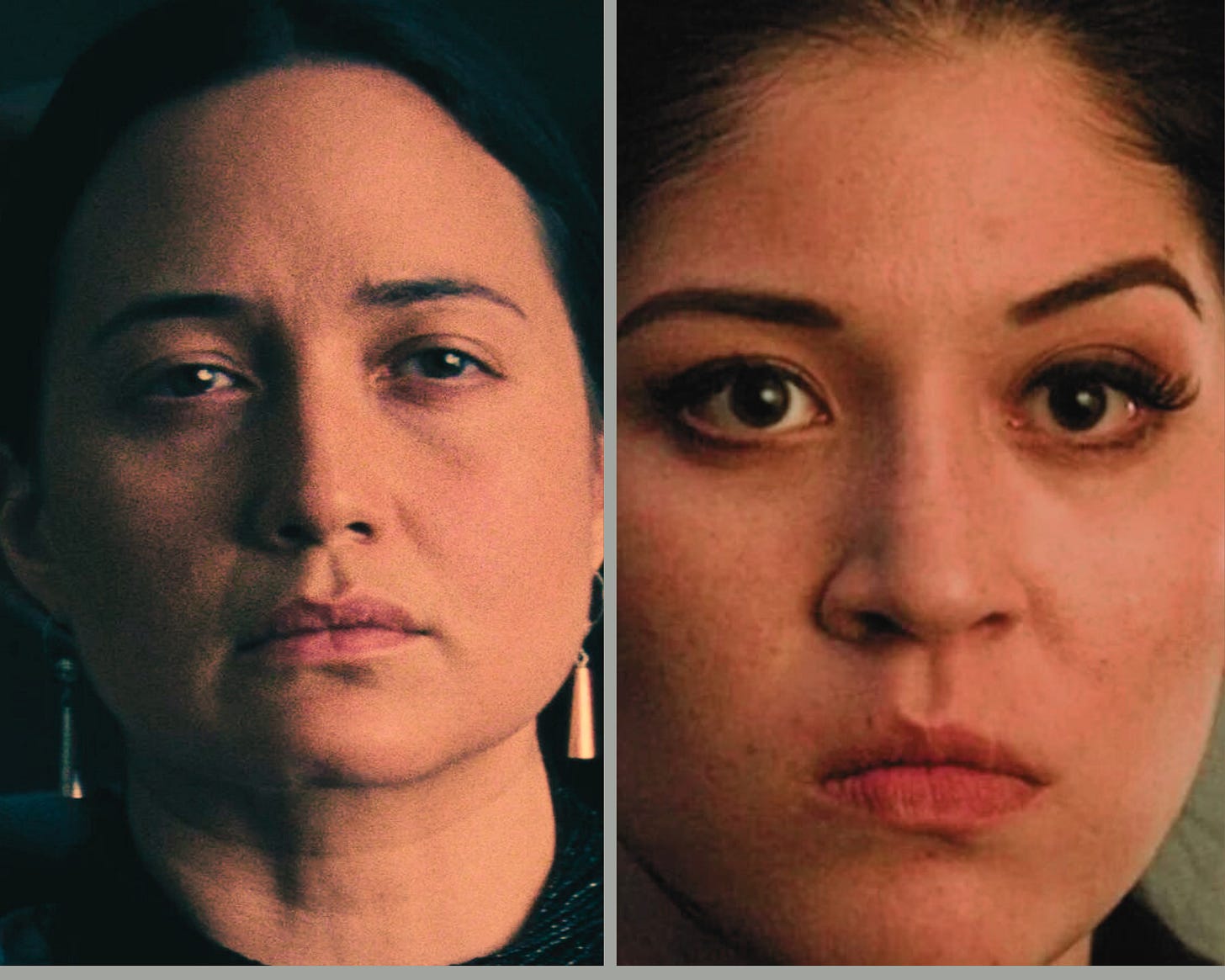

In an effort to gain a closer understanding about these matters, and the issue of Indigenous representation in the arts generally, I approached opera singer Melody Pilotte. I was put in touch with Melody by a colleague and am so grateful to her for her transparency, honesty, and her measured and thoughtful assessment of where we’re at in the culture. What follows are excerpts from our fascinating conversation.

Melody, thank you for sharing your thoughts and insights with me. What’s your background?

I am a Native/ Indigenous person, but I am not a tribal member of nations formally recognized by the United States. My biological father's tribe also does not recognize those who were born in the US and not Canada. My mother's people are Indigenous to Mexico (Nahua), and have no recognition in either the US or Mexico ( Indigenous people in Mexico, outside of a few tribal nations, are just seen as "Indigenous"--no special legal categories—they just exist, if that makes sense. I present as an Indigenous person and it's how I live my life and how I see myself; borders are imaginary and I wish we as Native/ Indigenous people would stop using them as ways to measure ourselves.

The reason I wanted to make sure I established my background is, because I am not enrolled in a US recognized tribal nation, I cannot 'market' myself or any art that I create as a "Native" (which, trust me, is as stupid as that sounds).

All that being said, I am a very proudly Indigenous person.

What did you think of the “We See You White American Theatre” manifesto?

It was very interesting going to sign it in June of 2020 and seeing a bunch of names on there of people who you know in real life are horrible to Black and Indigenous people, especially women. And this is not to say that it wasn't or isn't a wonderful idea, with many important and needed changes to be made, but Broadway just went back to business as usual, and anyone who said anything about it was treated like they were the problem.

As a person of Native American heritage, how do you feel about the practice of land acknowledgements and their proposed purpose? Do you feel they make a difference?

I think they are a good start; this is only the beginning baby step. We can't stop at land acknowledgements. Theatre companies have to also actively reach out to the people they are making acknowledgements towards, and engage with their elders and leaders about what they consider appropriate season rep, maybe hire them as sensitivity consultants. You know, humanize the people you're making broad gestures towards instead of having them be vague concepts.

What’s an alternative to the land acknowledgement practice which would more effectively raise awareness, visibility and opportunity for Indigenous people, particularly in theatre and the communities in which they are resident?

There has to be community engagement. It's so easy to Google your location and see who are the traditional custodians of the land, find tribal websites, and email or call folks. Heck, you could even request to visit, take them to lunch or something.

There are, as of last year’s demographic survey by the union, 79 members of Actor’s Equity (out of 51,000 active members) who identify as Native American.

There are only two people I can personally think of in AEA who are Native American, but I would consider there to be a lot more Indigenous people in AEA than people probably realize. Firstly, the 79 members probably only includes people who are members of United States federally recognized nations; this doesn't include people who are disenrolled, unrecognized, or Indigenous people and descendants from Central or South America or the Caribbean. Assimilation and detribalization is a hell of a drug.

Have you seen a surge in Indigenous representation in theater and other areas of entertainment? Native American actors being featured? Indigenous stories being told on stage and screen?

I think the rise of Native representation in the media is great! Part of me is a little skeptical, like it's just because these entertainment companies have learned they can make money off us, too (hahaha). I am glad that we are finally having a media moment, but I wish that shows like “Reservation Dogs” didn't leave out Afro-Indigenous representation. It costs us nothing to not leave anyone behind.

Some of the greatest performers of all time are our traditional storytellers and elders. The movie “Dreamkeeper” which came out in 2003 was really fun. My one concern with that is copyright and people trying to copyright our stories out from under us, and with bootlegging and things like that, some more sacred stories aren't meant for sharing.

We now have "Killers of the Flower Moon" out front and center as one of the most lauded and prestigious (and terribly upsetting and violent) films of the year. Lily Gladstone is superb and will surely win the Oscar.

I would love to see contemporary, positive portrayals of First Nations people. I fear that, like the Jews and the Holocaust, and African Americans and the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow, the stories of racism and injustice get told and should--but as a black actor friend of mine recently said, "It would be great to tell something other than PAIN." Do you agree?

I haven't seen "Killers of the Flower Moon" yet…I think it's probably too violent for me, if I am being honest…I absolutely agree, while these stories set in historical periods are important, it's also important to show us just living our lives!

Personally, I am more excited about “Echo” on Disney+ . I was a superfan of the Echo comics as a teenager and she's my favourite superhero. They went out of their way to cast a deaf Native actress and everything!

I know TikTok is a cesspool (I am mostly there for the farm videos), but there is a creator named Connor who is Lumbee and he talks about Native representation in media. He recently talked about the “Mean Girls” musical movie, and how there is an Indigenous character who just gets to be a character, and her heritage is just a footnote. I think Gabriel Iglesias has talked about that, too--not wanting to be "the Mexican comic," but wanting to be seen as a comic who is also Mexican (he's honestly probably the only comic I think is funny). That's how I feel, personally, about myself and my career, I think that my ethnicities are part of who I am, but they're a footnote as far as my career is concerned. I don't want to be the "Native" or "Indigenous opera singer," I want my abilities in my rare voice type to be what people talk about.

(To listen to Melody’s music, visit her website, and these two links.)

Melody points here to ideals of merit, excellence and achievement which, it seems, are secondary right now, with the emphasis in the culture on ticking boxes: putting more black and brown faces out there, or hyper-focusing on themes of injustice and oppression in BIPOC stories. Melody quite rightly wants to be recognized on the content of her character, her talent, and the contribution she makes to the world through her music. I very much hope that as we move forward through these fraught times—where the loudest voices dominating the cultural conversation belong to angry activists demanding demonstrations of contrition and atonement from “white oppressors”—that voices like Melody’s can be heard in all their richness, nuance, individuality, and yes, authentic expression of heritage and racial/ethnic pride.

While I respect Melody’s endorsement of land acknowledgments as a good “baby step,” to me talk is cheap. These recitations do little to nothing to help First Nations communities, and do absolutely zero to provide opportunity for Indigenous performers, playwrights and theatre makers. The demand of the We See You White American Theatre cabal has been met by theatre producers, but, I suspect, primarily out of a sense of obligation—or fear of retribution. If the land acknowledgement included an invitation to audiences to contribute toward the development of Indigenous themed plays and musicals, with the taking up of a collection as patrons leave the theatre (like Broadway Cares/EFA has done for years), or if a portion of ticket sales went toward scholarships for the training of young First Nations performers and storytellers, then real representation might take place. Until then, land acknowledgements have as much meaning as the famous crocodile tear streaming down the cheek of “pretendian” Iron Eyes Cody.

I didn’t realize it came to Broadway.

It is piety without faith, an endless eulogy to the failure to preserve culture performed at a cultural event, irony beyond comprehension.

No different than clasping hands at a prayer tent, pretending sincerity, counting the till.

Until indigenous populations start doing their own land acknowledgements to "honor" (or whatever is supposedly intended) the people that they displaced through violent conquest, I will go on believing that they're complete and utter BS. Human history is defined by people taking each other's land and resources if they can get away with it. Just because it happened to them during the relatively recent period known as "recorded history" does not put them in a separate, protected class and absolve their ancestors of basically doing the same things before the white man showed up. It's nothing but undiluted, performative hypocrisy - as if Native Americans all lived in peace and harmony with one another until Europeans came. News flash: they did not. They warred, kidnapped, raped and pillaged one another for thousands of years. Photographs and oral histories of their subjugation don't negate the atrocities they themselves committed before that technology was available on the continent.