It’s election day. The campaigns and the media are at fever pitch, warning that this is the most consequential election of all time. World War III and the apocalypse loom; disaster or survival depend upon which way the electorate’s 50/50 choice falls out. Every minute of every day, they’re “making us afraid of it, and telling us who’s to blame for it,” in the words of Aaron Sorkin. Armies of talking—nay, shrieking—heads invoke the classic bugaboos of ultimate evil—The Communists! The Nazis!—whilst conjuring up an array of all new grotesques, such as pet-grilling savages invading sleepy midwestern towns. Yeesh. It’s all hideous. Shameless, specious, sensationalist, propagandist bunkum whipping up hysteria on all sides. Hysteria is not a great place from which to make important decisions, and man, are we hysterical. Our public life is spiraling out. People need to get a grip.

I turned 59 last weekend. As I end my sixth decade, I’ve been musing upon how being an elder Gen X-er has shaped my character, my worldview, and my political outlook. I was listening to Shane Smith on The Joe Rogan Experience talking about being Gen X. He said, “It’s ironic, but Gen X actually lived in the greatest historical window of all time, potentially, so I’m not gonna not fucking enjoy that—I’m gonna go out into life.” Yep, we may be the “Forgotten Generation,” but we were lucky—I say that fully realizing that it’s hard not to come off like some sanctimonious, out-of-touch old guy, rhapsodizing about “back in the day.” But I think Gen X-ers have a valuable perspective to offer—the result of the times in which we grew up and came of age in America. Our lived experience. Perspective is a consolation we receive for getting older.

Now here’s a real kicker. This is the first Presidential election I’ve voted in where one of the candidates is my age. Kamala Harris just had a birthday too. She’s exactly one year older than I—a Boomer, technically—but we’re essentially of the same vintage. So, when I listen to Harris repeat her well rehearsed lines like ”I grew up in a middle class family,” and “my values haven’t changed”— I wonder: what are those values? Do I share some of them, having grown up in the same America at the same time? I’d like to believe, as Harris’s contemporary, that we share qualities characteristic of our generation: independent thought and freedom; self-starters with a passion for education, meritocracy and the pursuit of excellence; a realistic appreciation of diversity and a belief in equality.

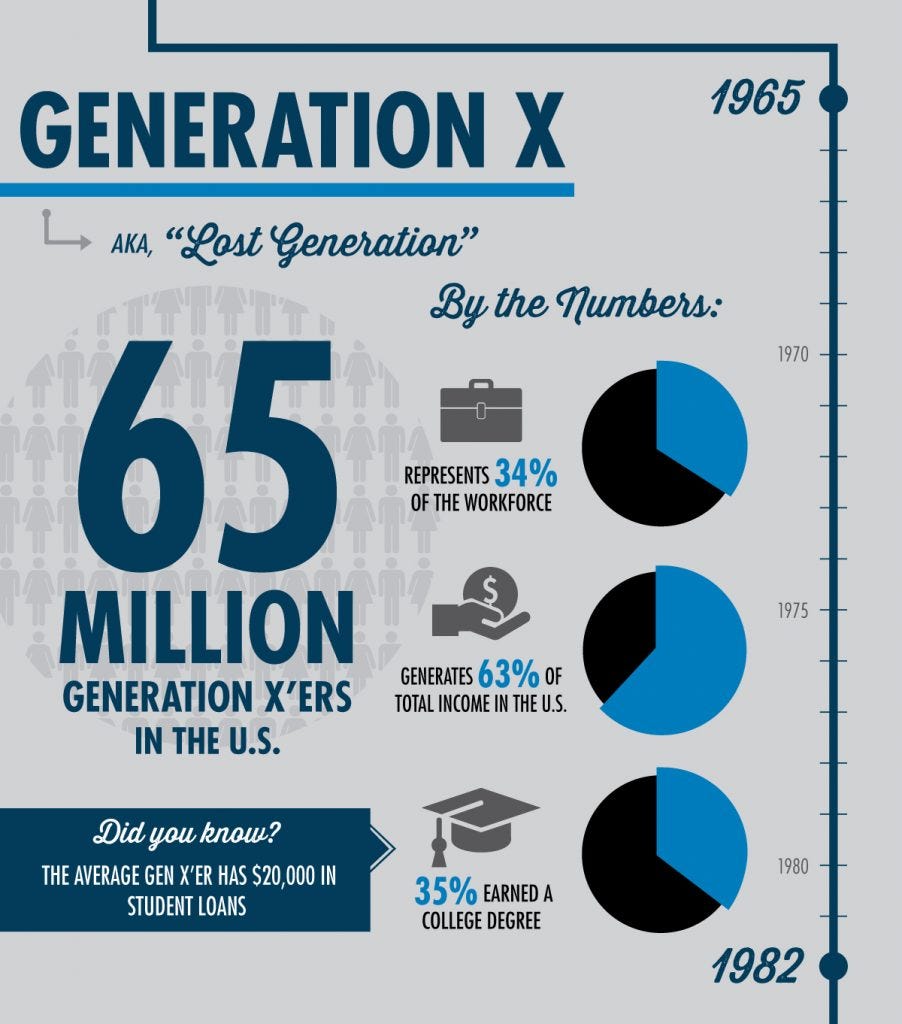

Generation X has been called “America’s Middle Child.” Born between 1965 and 1980, there are fewer of us than there are Boomers and Millennials—like, ten million fewer. We were the original “latchkey” kids, learning responsibility and self-reliance at an early age. Like Harris, I was a child of divorce; raised by a single mother. Like Harris, I looked after my little sister. I was the middle child of three—the “Jan Brady,” (for my fellow Gen X-ers). Fun fact: a few years ago did a musical with Eve Plumb, who played Jan on The Brady Bunch. During our first day meet-and-greet I told Eve, “You know, when I was a kid, I was you.” She drily quipped, “Funny. So was I.” But, I digress.

From a young age, I learned that if I wanted to see something, know something, or experience something, I had to seek it out. It was all “DIY.” My education was up to me. Luckily, my artistic parents surrounded us with music, art, and especially—books. Real books, with pages and everything. And not just for school—we read books recreationally. Today, we’ve lost the ability to read. The deterioration of basic reading skills amongst today’s kids is proof of it. I’m ashamed to admit it: I can’t remember when I last curled up with a good book. To read a book, one has to put all one’s focus on it. Multi-tasking while listening to an audiobook is not reading. We really didn’t multi-task as kids—we focused on one experience at a time, and reading was a daily activity. This helped me learn how to be present: to observe and listen, to concentrate.

Shane Smith referred to kids of our generation as “free range,” and I agree. We went outside. No adult supervision. We found things to do, games to play. For better or worse, we interacted with each other, sometimes coming home with bruised knees or hurt feelings, sometimes with a new friend. I know this all sounds very sentimental, but that’s how it was. We went outside. No parental supervision. We couldn’t be tracked with devices. Yet we somehow made it home in time for supper.

We had four television channels: the three major networks and PBS. Kamala Harris and I, and the rest of our generation, watched the same TV. There wasn’t right wing news, or left wing news, there was the news. We all watched the same prime time shows. I often get impatient when I hear young people railing on and on about diversity and representation on television as if there’s never been any. Anyone of my vintage who claims that there was no diversity on TV in the ‘70s—particularly in the representation of black people—is lying to you.

Here are just a few examples of mainstream shows that we all watched that featured black culture and black artists: Julia (featuring Diahann Carroll, the first black actress to star in her own TV drama, playing a working single mother), What’s Happening, Sanford and Son, The Jeffersons. Aside from workplace comedies like The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Barney Miller, and the various cop and detective shows, most sitcoms and dramas were family centered. And while my family couldn’t have been more different from the Evans family of the hit show Good Times, we watched faithfully. My family was even further from The Waltons or the Ingalls family of the Little House on the Prairie series, but I watched those families too—and I related to them. All these shows explored familial themes of parenting and growing up—whether in the hood or on the prairie—that were universal. Progressive kids’ shows like Sesame Street and Zoom had notably diverse casts. Who could forget Rita Moreno teaching us numbers in Spanish? Sure, it would be another couple decades before gay people would be represented fairly and honestly. It would take some time before TV shows would become more racially integrated, and tokenism less and less an issue. But don’t we still have “black shows” and “white shows?”

I wonder if Roots were produced today, on say, Netflix or BET, instead of airing as a mainstream miniseries event on ABC, if it would have the incredible impact it had in 1977. It was huge. We all watched it. And it wasn’t just race that was being represented. I grew up in the midst of the “Ms.” movement, with women like Gloria Steinem and Marlo Thomas redefining gender roles, breaking down barriers for women in politics and media. I’ve written about the album and TV special Free To Be…You and Me, which sought to take apart stereotypical gender roles for boys and girls, with an incredibly diverse cast of stars contributing their talents. As progressive as that was, I would guess that today’s leftists and gender ideologues would condemn it for reinforcing the gender binary (the first skit shows two puppet babies in a maternity ward—voiced by Mel Brooks and Marlo Thomas—discovering their puppet genitals for the first time), but for a little boy like me who liked to play with dolls, Free To Be…You and Me was a lifeline. I worry for the little gay boys of today. As a second or third grader, the first teasing I experienced from other kids came in the form of the question, “Are you a boy or a girl?” Of course I knew I was a boy—I never doubted that—I just couldn’t understand why all boys had to be the same. What legitimately concerns me for today’s kids is that if I were the little gay boy I was at a public school today, it might be some “queer” teacher asking me the question, “Are you a boy or a girl,” making me doubt my identity while dealing with just trying to belong. I guarantee you, if such a thing had happened when I was a kid, my mother would have come to school and ripped that teacher’s face off.

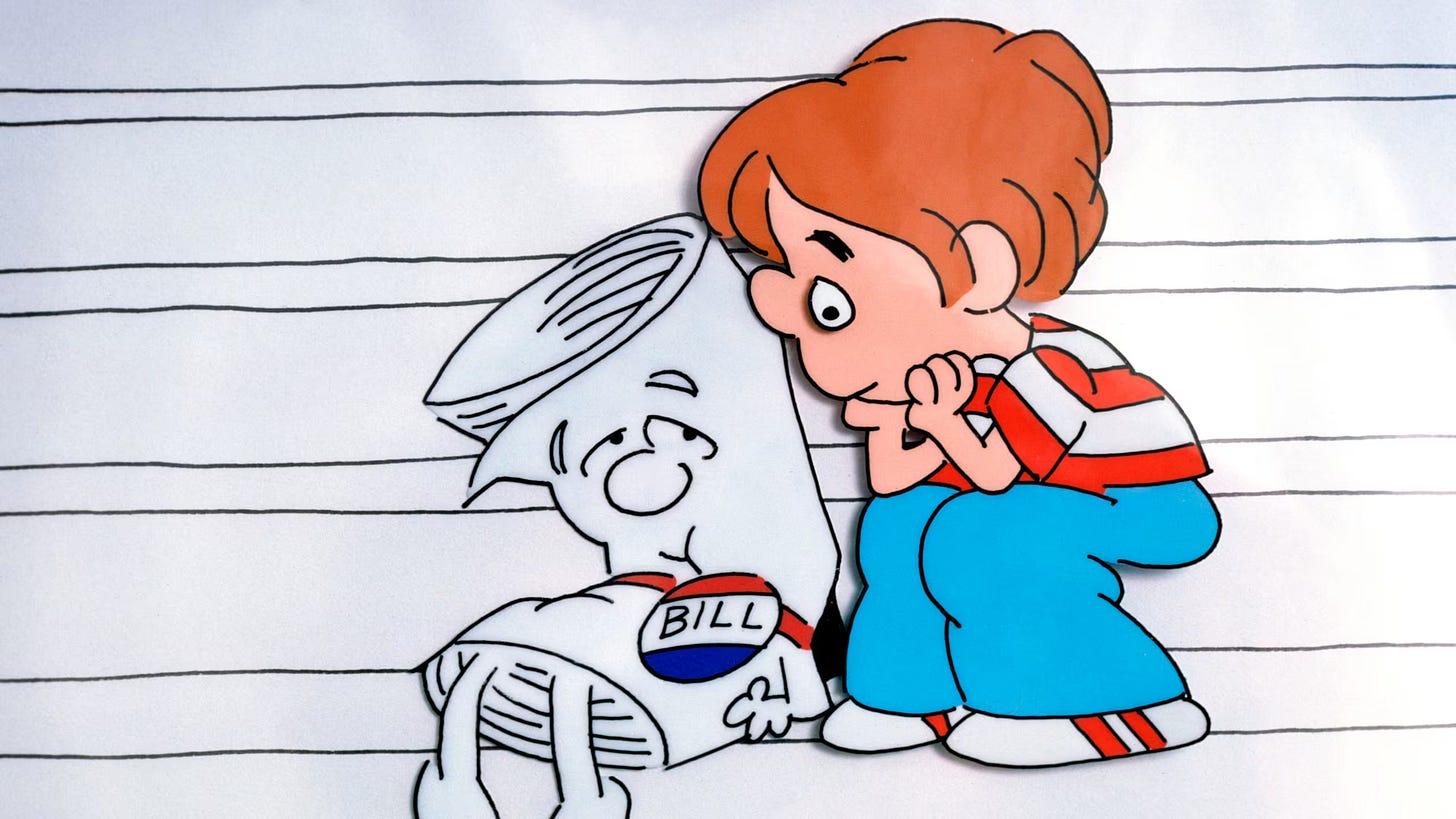

There was a common culture in America in those days. What 50-something can’t sing you the “plop-plop, fizz-fizz” jingle from the Alka-Seltzer commercial? What Gen X-er didn’t watch Saturday morning cartoons, where, between our favorite shows like Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids and H.R. Pufnstuf, we were treated to lessons in civics by Schoolhouse Rock? Ask anyone of my generation to recite the preamble to the Constitution and they will sing it to perfection! Ask them how a bill becomes a law and they’ll perform: “I’m just a bill, yes I’m only a bill, and I’m sitting here on Capitol Hill…” My point is, we all had a baseline understanding of how our government works, and what our duties as citizens were. As I wrote in a previous post, we all had a sense of what it meant to pledge allegiance to our flag and our country. We were all Americans, even though our union was far from perfect.

My family were total oddballs in the mostly white, mostly Catholic suburb of Boston I grew up in: a single Mom who started a grass roots theatre school, raising her Jewish kids, one of them a little gay boy, one adopted and black… we kinda were the diversity in our town. It’s different now of course. The local art school has taken over downtown Beverly, Massachusetts, bringing with it Crayola colored hair and nose piercings, and a rainbow flag flying over the Unitarian Church. We’ve come a long way, baby. But as weird and different as my misfit family were in that community nearly a half century ago, we still gathered with everyone else at Lynch Park every July Fourth for the outdoor band concert and fireworks. We were all Americans. There was a feeling that our American-ness bound us all together. We also watched those fireworks. We didn’t watch the fireworks together on our phones as each of us recorded ourselves watching the fireworks. That’s not the same. It’s just not.

My friend Sierra, a fellow Gen X-er, once observed, “We had analog childhoods and digital adulthoods.” As adults we had the opportunity to become tech savvy, not tech dependent. I was almost 40 when I joined Facebook with the rest of the world—I remember before social media. There’s no doubt in my mind that technology has overtaken us. The internet and AI have raced ahead of our ability to be ready for them and cope with their impacts. Our newfound interconnectivity has rendered us, ironically, more divided than ever. We have all created online avatar selves, complete with curated lists of identity, political, and ideological markers via which like-minded avatars can find us. We gather virtually under a hashtag or a flag and try to convince ourselves that it means we’re part of a “community.” This is an illusion. Such sprawling virtual masses of anonymous avatar people are not communities—at best, they are collectives. True community happens when we commune together. Real human interaction is what creates community.

There’s nothing that expands our view of ourselves and our world like interacting with people whose cultures and customs differ from our own. It is through such exploration that we come to learn what experiences are truly universal to all human beings. I have no children, and I would never presume to lecture anyone who has taken on the hardest and most important job in the world. But I would question parents of my generation who push for things like “safe spaces” and “affinity groups;” who have made their kids afraid, and sheltered them from confronting things that they find “uncomfortable,” inserting “sensitivity” readers, elaborate “community agreements,” codes of conduct, and trigger warnings between their kids and the world. When I was a kid, for better or worse, I walked into the unknown again and again, taking my experiences with others unfiltered—and learning to coexist with that which challenged and scared me. Gen X kids were taught to engage and to hold our own. No one wrapped us in bubble wrap. We didn’t walk into every new roomful of people treading on eggshells, wondering how to address them. Spaces became inclusive because we included ourselves, even when it was hard. I still live with the scars of a childhood spent being bullied and ostracized, but I’ll be honest with you—it made me strong and compassionate, and able to engage with anyone.

I would be hard-pressed to recommend that parents invest in college for their kids at this time. If they want to study medicine, or engineering, or chemistry, sure, of course. But we could produce more grounded, worldly, intelligent and discerning grownups if, instead of sending them to college at eighteen, we sent them out into the world. I say this fully realizing I’m an overeducated man with three college degrees who was raised by professional educators, but today’s young people don’t need to be isolated in ideological echo chambers on college campuses, where they’re encouraged not to be open-minded, but to be tribal and confrontational. Young adults need to learn how to live in the world, and they need to know this country and why it’s the greatest in the world. Because it is.

“Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one's lifetime.” – Mark Twain

Send them into the world, where they will have to engage with people whose lives are very different from their own. Encourage them to join the Peace Corps. Help them get certified to teach English as a second language. It will improve their own English skills, and provide them with paid employment while they travel or live in a new culture. I think we should expand Americorps. Instead of student loan forgiveness, provide college tuition at state schools to young people who contribute a year of their lives to service: building new affordable housing, cultivating community gardens, cleaning up urban neighborhoods, volunteering in hospitals, nursing homes and shelters. A new kind of G.I. Bill.

I could go on and on and on, and this is the reason it’s taken me over a month to publish this post! Here’s my final challenge to us all as we await the results of this insane election: go outside. Do it. Experience the world unfiltered, “unsafe,” and unrecorded. Go and touch grass. Go and touch grass and don’t bring your phone with you. Touch grass without taking a photo of it or shooting a TikTok video of it. Touch grass and when you come home, don’t post about the experience of touching grass. Take a real book with you and sit under a tree and lose yourself in it.

Walk into a restaurant you don’t know without googling it or reading any Yelp reviews. Sit down and ask the waiter to suggest their favorite things on the menu and let them order for you. Experience the food without taking a photo of it or a video of yourself eating it. And whether the dinner was good or not, don’t post your own Yelp review about it. Experience things for yourself—and eliminate your avatar audience. Try it. Let the experience of the place, the food, the people, be experienced—not performed, not recorded. You will learn just how addicted you are to social media.

I spent two years on the road with a big blockbuster Broadway show and played 62 cities throughout North America. I met, and interacted with, every kind of person and experienced nearly every corner and community of American culture. My conclusion was that most people are pretty great. I didn’t encounter many “garbage” people as I visited all but eight of these great states of ours. The only hope for America is Americans. The only things worth raising up are those things we all share in common. If we don’t reinvest in human interaction, communion, cooperation, and coexistence in this country, well…it really won’t matter who’s President. To quote a classic hit of the ‘70s, fittingly recorded by a group called Brotherhood of Man (sing along with me, my fellow Gen X-ers):

“For united we stand, divided we fall, and if our backs should ever be against the wall, we’ll be together, together, you and I.”

This is my 80th post at The Cornfield! Hard to believe I’ve had that much to say—and that I’ve said it—in an average of an essay a week over the past 19 months since joining Substack. I attempted a Cornfield podcast, recording a dozen episodes, and it was fun—but it proved too much for me logistically and financially. I don’t know what’s next for The Cornfield, but I’m up to over 600 subscribers—thank you! Consider a paid or free subscription, won’t you? Stay tuned and stay strong.

Happy (belated) Birthday 🎉🎂

I am also an older Gen-Xer. I am 58 (and a half 😝). I can totally relate to this post. Thank you!

Well said! This fellow Xer wishes you a vivid and meaningful 6th decade. Thanks for all you've shared.